What is Acoustic Neuroma?

An acoustic neuroma, also called a vestibular schwannoma, is a rare, non-cancerous tumor diagnosed in roughly 3,000 people per year in the US.

Each heading slides to reveal information.

Important Points

- They do not spread (metastasize) to other parts of the body. The brain is not invaded by the acoustic neuroma, but the tumor pushes on the brain as it enlarges.

- Acoustic neuromas constitute 8% of all brain tumors and are diagnosed in roughly 1 to 3.5 of every 100,000 people per year in the United States. This translates to about 2,500-3,000 newly diagnosed acoustic neuromas per year. Recent research has suggested that approximately one in 2,000 adults, and up to one in 500 adults over the age of 70, will be diagnosed with an acoustic neuroma during their lifetime.

- In most cases, these tumors grow slowly over a period of years, but sometimes the rate of growth is more rapid.

- Symptoms can be mild or severe and generally develop slowly, although occasionally symptoms might develop rather rapidly.

- The first signs or symptoms usually are related to ear function and can include hearing loss and/or tinnitus (ear noise/ringing in the ear) on one side.

- When large tumors cause severe pressure on the brainstem and cerebellum of the brain, vital functions that sustain life can be threatened.

- The most common method of diagnosing an acoustic tumor is by a detailed MRI of the head.

- The treatment options are observation (wait-and-scan), surgical removal, or radiation therapy. The choice of treatment may be based on tumor size, hearing in the ear at time of diagnosis, patient age and health, and patient preference.

Acoustic Neuroma vs. Vestibular Schwannoma

Originally these tumors were thought to arise from the cochlear (acoustic) nerve. With improved histopathology, they were determined to arise from the vestibular nerve, but the name acoustic neuroma stuck.

While the terms acoustic neuroma and vestibular schwannoma have been used interchangeably it is more pathologically correct that their name should reflect their nerve of origin and histopathology – hence the term vestibular schwannoma (VS).

A schwannoma, also known as a Schwann cell tumor, is a benign tumor that develops in the protective sheathing surrounding the nerve cells, called myelin. Schwann cells are the building blocks of that myelin, so schwannomas can develop anywhere Schwann cells are present. When a schwannoma develops in the Schwann cells of the eighth cranial nerve — also called the vestibulocochlear or acoustic nerve because it connects the ear to the brain — it is called a vestibular schwannoma (or acoustic neuroma). The tumor usually arises from the vestibular division of the vestibulocochlear nerve, rather than the cochlear division and it is derived from the Schwann cells of the associated nerve, rather than the actual neurons (neuromas).

Anatomy of an Acoustic Neuroma

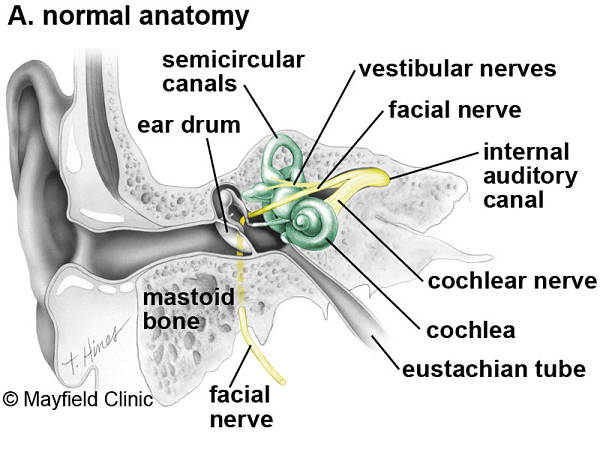

- An acoustic neuroma, known as a vestibular schwannoma, is a benign (non-cancerous) growth that arises on the eighth cranial nerve leading from the brain to the inner ear. This nerve has two distinct parts, one part associated with transmitting sound and the other with sending balance information to the brain from the inner ear.

- The eighth nerve, along with the facial or seventh cranial nerve, lie adjacent to each other as they pass through a bony canal called the internal auditory canal. This canal is approximately 2 cm (0.8 inches) long and it is generally here that acoustic neuromas originate from the sheath surrounding the eighth nerve. The seventh or facial nerve provides motion to the muscles of facial expression.

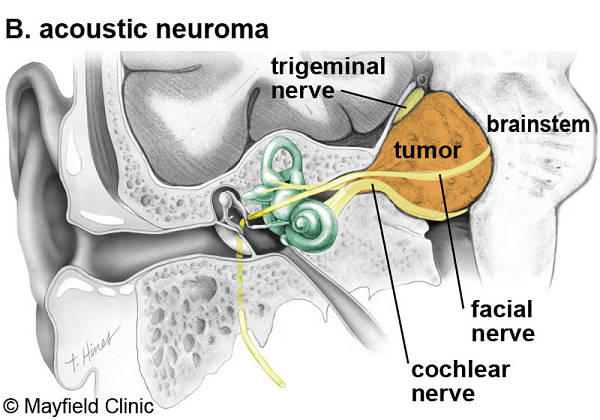

- Acoustic neuromas usually grow slowly over a period of years. They expand in size at their site of origin and when large can displace normal brain tissue as well as the facial nerve. The brain is not invaded by the tumor, but the tumor pushes the brain as it enlarges. The slowly enlarging tumor protrudes from the internal auditory canal into an area behind the temporal bone called the cerebellopontine angle. The tumor assumes a pear shape with the small end in the internal auditory canal.

- Larger tumors can press on another nerve in the area (the trigeminal nerve) which is the nerve of facial sensation. Vital functions to sustain life can be threatened when large tumors cause severe pressure on the brainstem and cerebellum.

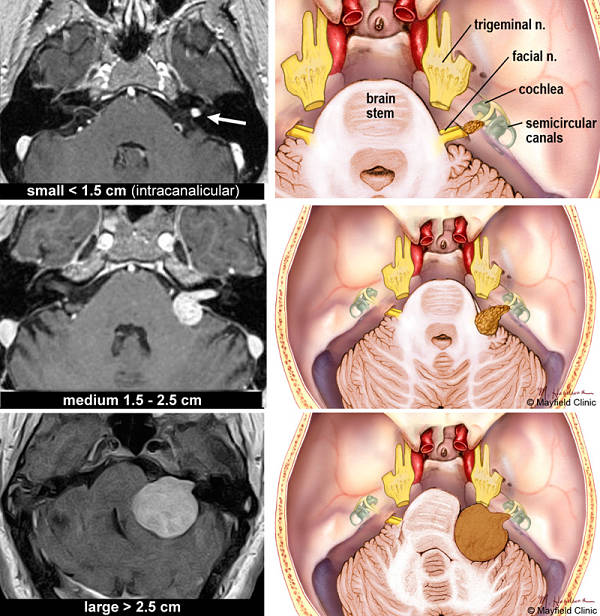

- Tumors are typically described as small (less than 2 cm), medium (2-4 cm) or large (more than 4 cm).

Anatomical Diagrams

Figure 1. The normal anatomy of the ear. The outer ear funnels sound to the eardrum, which vibrates three tiny bones called ossicles (malleus, incus and stapes). The spiral-shaped cochlea is filled with liquid, which moves in response to vibrations. As the fluid moves, thousands of hair cells are stimulated, sending signals along the cochlear nerve (responsible for hearing) to the brain. Attached to the cochlea are three semicircular canals positioned at right angles to each other. The three canals are able to sense head position and posture. Electrical signals from the semicircular canals are carried to the brain by the superior and inferior vestibular nerves (responsible for balance). The cochlear and vestibular nerves form a bundle inside the bony internal auditory canal. Inside the canal, the vestibulocochlear nerve lies next to the facial nerve (responsible for facial movement). (Printed with permission of the Mayfield Clinic – www.mayfieldclinic.com)

Figure 2. An acoustic neuroma expands out of the internal auditory canal displacing the cochlear, facial and trigeminal nerves located in the cerebellopontine angle. Eventually the tumor can compress the brainstem. (Printed with permission of the Mayfield Clinic – www.mayfieldclinic.com)

Figure 3. Acoustic neuromas are classified according to their size. MRI scans and correlative illustrations of small (intracanalicular), medium and large acoustic neuromas. (Printed with permission of the Mayfield Clinic – www.mayfieldclinic.com)

Types / How Common is Acoustic Neuroma?

Unilateral (one side) ANs occur spontaneously without any evidence of family history, and account for 95% of acoustic neuromas

Bilateral (both sides) ANs are most likely caused by a genetic condition called Neurofibromatosis Type 2 (NF2) which affects approximately 1 in every 40,000 people. NF2 will be suspected if a parent/sibling/child of the patient has NF2 and acoustic neuroma occurs before age 30 or if the patient has had a meningioma, glioma, or cataract.

Most recent publications suggest that the incidence of acoustic neuromas is rising. This is because of advances in MRI scanning both on incidental scans and for patients experiencing symptoms. It is estimated that the instances of acoustic neuroma diagnosis are between 1 to 3.5* in every 100,000 per year.

*In your research you may find differing statistics on acoustic neuroma occurrence. ANA provides a range that is inclusive of data from medical center websites and research studies.

Acoustic Neuroma Causes

The cause of acoustic neuroma is not well understood. Virtually all acoustic neuromas have at least one mutation involving an important gene located on chromosome 22. When this gene is healthy, it prevents the Schwann cells from growing into a tumor. When this gene is mutated, the result can be a “wart-like” growth of these cells to produce the neuroma.

For the most part it is not an inherited disease; however, 5% of cases are associated with a genetic disorder called neurofibromatosis type 2. These individuals demonstrate two-sided vestibular tumors often associated with other tumors around the brain and/or in the spine. The vast majority of acoustic neuromas are sporadic (nonhereditary).

There is no convincing evidence that certain foods, smoking, or other environmental factors increase the risk of developing an acoustic neuroma.

What Determines the Symptoms?

Symptoms can be associated with the size of the tumor but this is not always consistent. Some patients experience few symptoms despite the presence of a large tumor. Small tumors are defined at 2 centimeters or less, medium tumors are between 2 and 4 centimeters, and large tumors are over 4 centimeters. Smaller tumors can often be associated with few symptoms whereas large compressive tumors can be life threatening.

Neurofibromatosis (NF2)

NF2, a genetic disorder, occurs with a frequency of 1 in 30,000 to 1 in 50,000 births. The hallmark of this disorder is bilateral acoustic neuromas (an acoustic neuroma on both sides).

Patients with NF2 should seek care from an NF2 treatment center with a very experienced multidisciplinary team that provides comprehensive care to address all aspects of the condition. There is no cure for NF2 but doctors may recommend treatments such as surgery, radiation, or chemotherapy customized for each patient and their individual circumstances.

Bilateral acoustic neuromas creates the perplexing problem of the possibility of complete deafness if the tumors are left to grow unchecked. Preventing or treating the complete deafness that may befall individuals with NF2 requires complex decision making. The trend at most academic U.S. medical centers is to recommend treatment for the smallest tumor which has the best chance of preserving hearing. If this goal is successful, then treatment can also be offered for the remaining tumor. If hearing is not preserved at the initial treatment, then usually the second tumor, in the only-hearing ear, is just observed. If it shows continued growth and becomes life-threatening, or if the hearing is lost over time as the tumor grows, then treatment is undertaken. This strategy has the highest chance of preserving hearing for the longest time possible.

There are now several options to try to rehabilitate deafness in NF2 patients. Implanting the hearing part of the brainstem (Auditory Brainstem Implant) can help restore some sound perception to these patients. Also cochlear implants can be used if the cochlear nerve is preserved following surgery. Radiosurgery may be an option although stereotactic radiosurgery may not have the same effect on the NF2 patient as in patients with unilateral sporadic tumors. There are some centers using radiation therapy for NF2 with mixed results. The risk of malignant transformation after radiation is higher in this group. Recent studies have shown that these individuals may have more tumors that are resistant to radiation, due to the cell type.

For more information, visit nfnetwork.org.