Surgery

Surgery Basics

Physicians may choose surgery for people with large tumors or tumors that are causing serious problems with balance, persistent headaches or facial pain, or hydrocephalus, a buildup of fluid in the brain.

Hydrocephalus occurs when an acoustic neuroma grows large enough to press on the brain stem, the lower portion of the brain that connects to the spinal cord. This blocks the flow of cerebrospinal fluid—the liquid that surrounds and cushions the brain and spinal cord—from draining properly.

Very small tumors can also be treated with surgery when doctors observe growth or when preservation of hearing is a goal.

Surgery to remove an acoustic neuroma is often guided by computer software that incorporates MRI scans and CT scans, which create three-dimensional images of the brain. The imaging tests help surgeons remove tumors with great precision, while avoiding damage to nerves responsible for hearing, balance, and facial movement.

Surgical Approach Overview

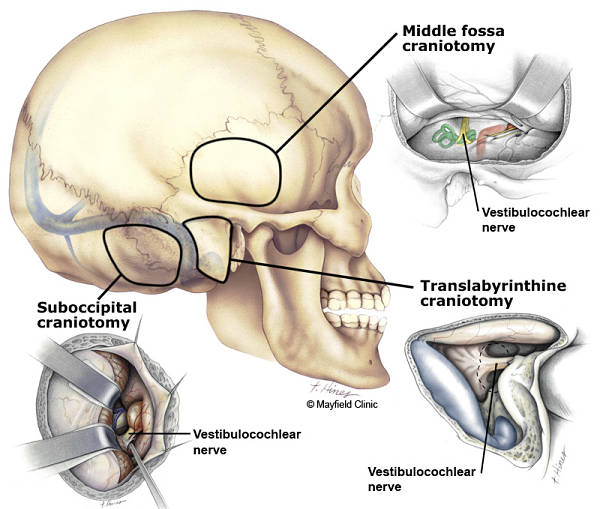

How do you decide which type of surgery is right for you? The surgical approach your doctor uses depends on the tumor size and location and whether preserving your hearing is a priority or an option. All procedures require general anesthesia.

The surgery is performed by a team of physicians including a neurotologist (ear and skull base surgeon) and a neurosurgeon. There are three main microsurgical approaches for the removal of an acoustic neuroma: translabyrinthine, retrosigmoid/sub-occipital and middle fossa. The approach used for each individual patient is based on several factors such as tumor size, location, skill and experience of the surgeon, and whether or not hearing preservation is a goal. The surgeon and the patient should thoroughly discuss the reasons for a selected appoach. Each of the surgical approaches has advantages and disadvantages, and excellent results have been achieved using all three of the techniques.

Figure 2. Three surgical approaches to an acoustic neuroma: retrosigmoid/sub-occipital, translabyrinthine and middle fossa.

(Printed with permission of the Mayfield Clinic - www.mayfieldclinic.com)

Translabyrinthine Approach

Doctors may use translabyrinthine surgery for any size of tumor that has caused significant hearing loss or where hearing preservation is not possible. During this procedure, the surgeon makes an incision behind the ear and opens the mastoid bone, as well as a portion of the inner ear, which contains structures important for hearing and balance. This gives the surgeon access to the tumor in the internal auditory canal, which acts as the passageway for the eighth cranial nerve—the nerve that runs from the brain to the inner ears—and provides a good view of the nerves so the surgeon can preserve facial function.

The surgeon removes the entire tumor, or as much of it as is safely possible. To reach the tumor, surgeons occasionally remove the cochlea, the part of the inner ear that processes sound, or the otic capsule, which is the bony structure that surrounds the inner ear.

Because a portion of the inner ear is removed during this procedure, hearing is lost in that ear. Balance is usually not a problem because the opposite ear can take over this function, although rehabilitation therapy may be necessary to help you compensate for some loss of balance.

In general, the translabyrinthine approach is the best option when hearing has already been severely affected from the tumor or when tumors are large and hearing preservation is not possible.

Retrosigmoid Approach

Surgeons may use a retrosigmoid approach for smaller acoustic neuromas when hearing preservation is possible. They use this approach for tumors that are growing out of the internal auditory canal and approaching the brainstem.

During this surgery, a surgeon makes an incision further behind the ear to open a portion of the skull called the occipital bone, located behind the mastoid. The cerebellum, a part of the brain located above the brain stem, falls back out of the way, and surgeons remove the bone over the internal auditory canal to fully access the tumor. The surgeons can view the facial nerve, the hearing nerve, and the brainstem.

If removing the entire tumor could damage nerves or brain tissue, the doctor may leave some small bits of the tumor behind. The section of the skull opened to perform this surgery is replaced after tumor removal. Fat from the periumbilical region, meaning the area surrounding the belly button, may be removed and used to seal the closure to prevent spinal fluid leaks.

Middle Fossa Approach

The middle fossa approach is an option for smaller tumors that have not grown beyond the internal auditory canal. As with the retrosigmoid approach, it is used to help preserve hearing. The surgeon makes an incision above the ear in the lateral skull bone, and then uncovers the internal auditory canal, and removes the acoustic neuroma. Then surgeons replace the skull bone and use fat from elsewhere in the body to help close the opening. This approach is the best for saving hearing, which is possible in the majority of people who have the procedure.

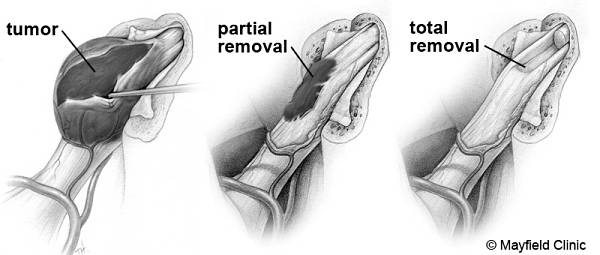

Subtotal, Near Total and Total Removal

Subtotal Removal:

Subtotal removal is indicated when anything further risks life or neurological function. In these cases the residual tumor should be followed for risk of growth (approximately 35%). If the residual tumor grows further, treatment will likely be required. Periodic MRI studies are important to follow the potential growth rate of any tumor.

Older patients with large tumors causing a threat to life may elect to have their surgeon sub-totally remove their tumor. Partial tumor removal has also been advocated in some patients who have large tumors in their only hearing ear. This surgical management will reduce the tumor in size, so that it may cause no threat to the patient's health during his or her life expectancy. This approach may reduce the probability of facial nerve dysfunction as a result of the surgery.

Near Total Tumor Removal:

This approach is used by experienced centers when small areas of the tumor are so adherent to the facial nerve that total removal would result in facial weakness. The piece left is generally less than 1% of the original and poses a risk of regrowth of approximately 3%. Periodic MRI studies are important to follow the potential growth rate of any tumor.

Total Tumor Removal:

Many tumors can be entirely removed by surgery. Microsurgical techniques and instruments, along with the operating microscope, have greatly reduced the surgical risks of total tumor removal. Preservation of the facial nerve to prevent permanent facial paralysis is the primary task for the experienced acoustic neuroma surgeon. Preservation of hearing is an important goal for patients who present with functional hearing. Both facial nerve function and hearing is electrically monitored during surgery. This is a valuable aid for the surgeon while the tumor is being removed.

Figure 1. Comparison of partial and total tumor removal. Every effort is made to remove the tumor without damaging the adjacent nerves or vital brainstem functions. Sometimes it may be best to leave small pieces of tumor capsule attached to critical structures rather than risk damage. If over time the tumor remnant grows, futher treatment is warranted. (Printed with permission of the Mayfield Clinic – www.mayfieldclinic.com)

What to Expect after Surgery

After surgery, you may spend a few days recovering in the hospital while your doctor monitors you and manages any pain, dizziness, and other symptoms you may be experiencing. If your hearing has been affected by the surgery, your doctor can work with you to explore your options for hearing rehabilitation. Balance is recovered slowly, and most people can return to work in 8 to 12 weeks.